The information provided in this article is for informational purposes only and should not be considered as investment, tax, or financial advice. While we strive to provide accurate information, we cannot guarantee its accuracy or completeness. You should always consult with a qualified financial advisor or professional before making any investment decisions.

In a previous post, we discussed the differences between recent tokenized stock offerings and Permuto Capital AC/DC certificates and concluded the two types of products serve different purposes and cover different equities. In this post, we will look at a historical product that is much more similar in nature to Permuto Capital’s Asset and Dividend Certificates: Americus Trust PRIMEs/SCOREs.

What were the Americus Trusts?

Introduced in 1983 by Americus Shareholder Services Corporation, the Americus Trusts allowed shareholders to deposit a share of common stock and receive two tradable securities in return, a PRIME and a SCORE:

- PRIMEs (Prescribed Right to Income and Maximum Equity) offered dividend and voting rights, plus capital appreciation up to a capped amount until a 5-year termination date.

- SCOREs (Special Claim on Residual Equity) captured any appreciation above that cap again up to a 5-year termination date.

These were traded separately on AMEX, the American Stock Exchange (now known as NYSE American). Americus created a total of 27 trusts each lasting 5 years, starting with AT&T in 1983, and ending with the last trust, American Express, expiring in 1992. There were a number of household names included in the full list of 27 trusts issued between 1983 and 1987 (Cheong et al., 1991):

- 1983: AT&T-Series A

- 1985: Exxon

- 1987: American Express, American Home Products, AT&T-Series 2, Amoco, ARCO, Bristol Myers, Chevron, Coca-Cola, Dow, DuPont, Kodak, Ford, GE, GM, GTE, Hewlett Packard, IBM, Johnson & Johnson, Merck, Mobil, Philip Morris, Procter & Gamble, Sears, Union Pacific, and Xerox.

Interestingly, 31 trusts were initially proposed but 4 of them ultimately did not launch (Barber, 1994):

- Schlumberger Ltd. and Royal Dutch/Shell Group due to questions about tax implications involved with foreign securities.

- Texaco and 3M due to not reaching AMEX minimum listing requirements at offering (see below for more about listing requirements).

How popular were Americus Trusts?

Prior to launch, the idea of PRIMEs and SCOREs was met with mixed response. Here are excerpts from a New York Times article on the launch of the Americus Trust for Exxon (Wallace, 1985).

Many professional investors find the trust concept appealing. Eric Seff, vice president at the Chase Investors Management Corporation, sees the components as a ”more efficient” way to buy stock, much like an option or other derivative investment vehicles.

Michael Lipper, president of Lipper Analytical Securities in New York, said that because he has been satisfied with dual-purpose funds he is inclined toward this kind of investment. But he cautions that like dual-purpose funds, the components may trade at a discount because of little demand. His chief concern is whether there will be enough secondary trading to create demand for the units and components. ”I don’t know that there will be much in the way of a secondary market,” he said.

Americus officials may have a tough sell on their hands regarding the large institutional investors. So far, the trust has not grabbed their imagination. A portfolio manager with a large New York firm and a Texas-based investment manager both said they knew very little about the trust, but probably would not invest in it. And a fund manager of one of the largest growth stock mutual funds said that he had no interest in such a concept.

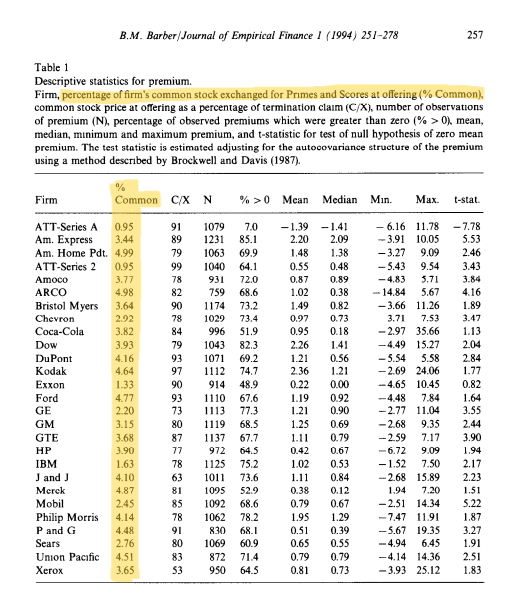

After launching, the data tells a clearer story. Excluding the AT&T Series A and Series 2 Trusts as there is likely confounding with the divestiture of AT&T in 1984, the remaining 25 trusts had at least 1.33% of the common stock deposited into the trust with 6 trusts over 4.5% at offering: American Home Products, ARCO, Kodak, Ford, Merck, Union Pacific (Barber, 1994).

From the literature and articles there are other things we know about PRIMEs and SCOREs:

- Two trusts, Texaco and 3M, failed to meet initial listing requirements (Barber, 1994)

- By 1991, PRIMEs and SCOREs accounted for 10% of the trading volume on AMEX (Huckins, 1995)

- They often dominated the AMEX lists of daily gainers and losers (Norris, 1992)

- Many traded at a premium to the underlying stock (Cheong et al., 1991) which created an arbitrage to tender shares to the trust until the trust was “closed” by virtue of hitting its 5% cap.

Overall, there was significant demand for these products even at offering — enough so that both the SEC and IRS enacted rule changes around them.

Why did the Americus Trusts Fail?

In short, IRS tax law changes. Understanding the tax law changes around the Americus Trusts are a bit complicated, but here’s a brief timeline based on an 1985 SRO document from the SEC (Securities and Exchange Commission, 1985) including page references to this document:

- September 1980: The IRS issued a private letter ruling stating Americus Trusts would be treated as a grantor trust for federal tax purposes (page 2), ensuring pass-through taxation without the trust itself being taxed and making the trust structure financially viable. The ruling also stated no gain or loss recognized upon deposit of a share.

- April 1984: In response to Americus filing registration statements for further trusts, the IRS revoked their 1980 private letter ruling (page 2) and proposed to classify Americus Trusts as associations rather than grantor trusts, subjecting the trusts themselves to federal income taxation as a corporation thus reducing their appeal to investors due to double taxation (Jarrow and O’Hara, 1989).

- June 1984: Americus opposed the IRS proposal and argued for their already-filed trusts with the SEC to be “grandfathered” to the 1980 ruling (page 6, footnote 10).

- July 1984: The NYSE imposed a moratorium on listing additional Americus Trusts (page 2, footnote 12).

- November 1984: The IRS issued a supplementary ruling allowing Americus to be grandfathered to the 1980 ruling, temporarily resolving tax uncertainty and enabling Americus to pursue listing on AMEX instead of NYSE for their already-filed trusts (page 2, footnote 11).

These rulings meant the 30 already-filed Americus Trusts (of which they ultimately launched 27) would be the last Americus Trusts subject to the more favorable tax classification of the 1980 private letter ruling. This, coupled with the 1987 market crash led to the trusts’ extinction by 1992 (Norris, 1992).

What is the Legacy of Americus Trusts?

Despite their extinction, Americus Trusts left a lasting impact as they led to IRS and AMEX rule changes, inspired a number of financial instruments that attempted to provide similar flexibility to investors, and became a unique source of data for academic research.

New AMEX Listing Standards

Specific listing standards for investment trusts were created by the American Stock Exchange (now NYSE American) and approved by the SEC in 1985 (Securities and Exchange Commission, 1985), many of which are still in effect today:

- Issuers of underlying securities must have total assets over $100 million and net worth over $10 million.

- Trusts must have a minimum public distribution of one million units held by at least 800 round-lot holders (p. 1).

- Trusts must have a minimum term of three years (p. 1).

- Only one trust per security, with a cap of 5% of an issuer’s securities held by a trust, and a prohibition on trusts holding Amex-listed securities (p. 1, 5).

- Trusts must pass through voting rights to unit holders and provide shareholder communications if reimbursed by the issuer (p. 1, 4).

The last two rules in particular were meant to mitigate concerns around market confusion, liquidity, and corporate governance. The fear was that multiple similar trusts on the same equity would not only create investor confusion but also fragment the liquidity in the market for a particular stock (hence the minimum size requirement of the underlying security as well).

At the time, creating PRIMEs and SCOREs for a company would essentially take one liquidity pool (of the common stock) and split it into 3 liquidity pools (common stock, PRIMEs, and SCOREs). The concern was that uncapped trust holdings or allowing more than one trust per security could negatively impact market efficiency.

Influence on future financial instruments

The new listing standards contributed to the evolution of exchange rules for other structured investment products and even influenced modern exchange-traded products like ETFs by establishing criteria for transparency, liquidity, and investor protection.

The idea of decomposing a stream of returns has been widely incorporated in other derivative instruments like USUs (Unbundled Stock Units), LEAPs (Long-term Equity Anticipation Securities), BOUNDS (Buy-write Option UNitary DerivativeS), PERCS (Preferred Equity Redemption Cumulative Stock), and others (Canina, 1996).

Tool for Academic Research

The decomposition of a stock into PRIMEs and SCOREs created unique data for academic research to gather insight into a new dimension of the market. For example, there were papers on how to value each component (Huckins, 1995), how earnings announcements impacted each component (MacDonald and Smith, 1999), and the observation that the combined value of PRIMEs and SCOREs was often higher than the underlying (Cheong et al., 1991; Jarrow and O’Hara, 1989) to name a few.

How do Permuto Capital AC/DCs compare?

With Permuto Capital’s take on unbundling a stock into AC (Asset Certificates) and DC (Dividend Certificates), there are a number of important differences to highlight when compared to PRIMEs and SCOREs.

As they are described, Permuto Capital AC/DCs:

- Have a favorable tax treatment

- Have a different fee structure

- Have a simpler and perpetual structure (don’t expire after 5 years)

- Will be tradable on Chia Blockchain in addition to NYSE American

Favorable Tax Treatment

If we assume the Permuto Trusts can operate as a partnership with a Qualifying Income Exception as it intends, then it will be subject to similar favorable tax treatment as the original Americus Trusts under the grandfathered 1980 IRS private rulings described previously. Reasons for this classification and consequences for not being treated as such is covered in the “UNITED STATES FEDERAL INCOME TAX CONSIDERATIONS” section of the most recent Permuto Trust S-1 filings.

Americus Trusts losing this favorable tax treatment was a reason for its extinction and Permuto Capital’s different trust and operating structure aims to receive this favorable tax treatment under existing tax law, specifically Section 7704.

There are tax-related similarities as well, like how both Americus and Permuto trusts would withhold 30% of payouts for the IRS unless a US holder provides a tax identification number or a non-resident submits an IRS form to engage a relevant tax treaty.

Different Fee Structure

A trust has a few main places to take a fee: deposit, redemption, and dividends. Americus Trusts opted to take a flat fee per share for deposits and dividends whereas Permuto Capital opts to take a percentage. Americus Trusts’ exact fee amounts differed for each trust but we’ll take their Exxon trust as an illustrative example (Americus Shareowner Service Corporation, 1985).

| Fee | Americus Trusts (Exxon) | Permuto Capital Trusts |

|---|---|---|

| Deposit Fee | 1.5%* ($0.78 per share) | 0.5% |

| Redemption Fee | None | 1% |

| Dividend Fee | 12%** ($0.05 per PRIME/year) | 20% on DTC 10% on Chia blockchain |

**dividend fee percentage based on trailing 12 month dividend amount of Exxon stock on Feb 1986 from WallStreetNumbers.com.

The types of expenses in running a trust in the 1980’s compared to now are likely different but we can see the fees charged are similar. Interestingly, the deposit and redemption fees total the same at 1.5% combined.

Expenses to administer dividend payouts and tax documents for DCs held on the Chia blockchain are expected to be significantly cheaper than those held on DTC and reflected in the difference in dividend fees between the two. However, it would not surprise me to see these fees be adjusted for subsequent trusts once Permuto Capital has a better understanding of uptake and costs with their initial trusts.

Simpler and Perpetual Structure

PRIMEs/SCOREs had a fixed term duration (non-perpetual) and had a complex structure that made valuation more challenging. Specifically, PRIMEs did not solely represent the dividend cash flow due to the additional capital appreciation up to a termination amount.

On the other hand, ACs and DCs are simpler to understand. They are perpetual certificates and dividends are paid to DC holders — the pricing of ACs and DCs is simply left to the market depending on how they value the yield and risk. I shared one possible valuation model in a previous post. Other valuation models have been published including tools/calculators:

- Growing Annuity and Simple Yield Target models from DrugAnalyst

- Growing Annuity model from Green Brick Road

The perpetual nature of AC/DCs will also allow them to be held by long-term dividend investors without fear of reinvestment risk. It also makes them more straightforward to be packaged into an ETF to create a diverse basket of DCs in order to hedge against company or industry risk that might lead to dividend cuts. Note that ETFs did not exist during the period of PRIMEs and SCOREs.

Tradable both on-chain and on NYSE American

The ability to trade (and hold) AC/DCs on the Chia blockchain allows for lower fees and thus higher potential yields than even the Americus Trusts, while also creating a globally accessible market for 24/7 trading.

Pricing differences and arbitrage opportunities will exist between the two venues due to cost, liquidity, as well as operating hours. This leads to market making opportunities that can potentially drive both on-chain and off-chain volume.

What does this mean for Permuto Capital?

The history of Americus Trusts indicates there is demand for such an unbundled product from both the market as well as the exchanges.

The Exchanges, for some time, have sought a replacement for the expired Americus Trust PRIMEs and SCOREs. During this process, the Exchanges began to list and trade a standardized option product called LEAPs. Like SCOREs, LEAPs enable investors to receive the benefits of a stock’s price appreciation above a fixed dollar amount over a long period of time. Currently, however, there is no generally available replacement for the PRIMEs component.

(Securities and Exchange Commission, 1996)

There are other aspects of the Americus Trusts journey in which Permuto Capital could follow suit (some personal speculation follows):

- Launch with a single trust, and increase quickly: Americus Trusts initially started with just AT&T and Exxon trusts, followed by quickly filing the remaining 27+ trusts. Permuto Capital has stated they are looking to start with just Microsoft in the next months and aim to launch 20+ trusts by the end of the year and 85+ in time.

- Quickly get to a significant % of common stock: Americus Trusts had several trusts that were near the 5% cap at offering. I wouldn’t be surprised to see some Permuto trusts quickly get near 5% as well but maybe not right at offering due to a different direct listing approach.

- Stick with US companies to start: Americus Trusts withdrew a couple foreign (non-US) company trusts due to uncertainty around tax regulation. I also don’t expect Permuto to go after foreign companies — at least not initially.

- Not all trusts will be successful: There were a couple Americus Trusts that failed to meet listing requirements. Some smaller Permuto trusts may face the same challenge though the recent amendment to issue 100 AC/DC units per deposited share does help with meeting the minimum unit requirement.

- Tax treatment matters: The tax classification and treatment was the difference between success and failure for the Americus Trusts. Tax law related discussions will be important for Permuto Capital to address with both customers and regulators.

- Be the only trust for a given stock: The 1985 SEC rule change indicated a desire to limit fragmentation of liquidity and only allows one trust per security on AMEX. Permuto Capital would be highly motivated to file and launch their trusts quickly in order to establish themselves as the sole trust to unbundle dividend-paying stocks. I also don’t foresee the SEC changing their position here as liquidity fragmentation has only grown as a concern due to the rise of ETFs/ETPs since the 1990s.

- The combined unit trades at a premium: Research showed that the sum of the unbundled components often traded at a premium to the underlying. This is something that could translate to AC/DCs and such a premium could potentially drive each trust to their 5% cap quickly due to arbitrage.

Time will tell whether the Permuto Capital trusts have necessary regulatory approval and market interest to launch. And if they do, I’m curious to see how the market prices and trades the unbundled components.

I’ll just end by paraphrasing Mark Twain, “History doesn’t repeat itself but it often rhymes.”

References

- Americus Shareowner Service Corporation. (1985, August 16). Americus Trust for Exxon Shares Prospectus.

- Barber, B. M. (1994). Noise trading and prime and score premiums. Journal of Empirical Finance, 1(3-4), 251–278.

- Canina, L. (1999). The market’s perception of the information conveyed by dividend announcements. Journal of Multinational Financial Management, 9(1), 1–13.

- Cheong, M. K., Finnerty, J. E., & Park, H. Y. (1991, October). The premiums of SCOREs and PRIMEs: A further investigation of transaction cost saving hypothesis (Faculty Working Paper 91-0174).

- Huckins, N. W. (1995). Repackaging cashflows and the creation of value: The case of primes and scores. International Review of Financial Analysis, 4(2–3), 123–142.

- Jarrow, R. A., & O’Hara, M. (1989). Primes and scores: An essay on market imperfections. The Journal of Finance, 44(5), 1263–1287.

- MacDonald, J. A., & Smith, D. M. (1999). Investor partitioning of the components of value in corporate earnings announcements. Financial Services Review, 8(2), 87–99.

- Norris, F. (1992, February 13). Market place; Americus Trust becoming extinct. The New York Times.

- Securities and Exchange Commission. (1985, March 18). Self-regulatory organizations; American Stock Exchange, Inc.; Order approving proposed rule change (Release No. 34-21863; 32 S.E.C. Docket 919).

- Securities and Exchange Commission. (1996, January 23). Self-regulatory organizations; American Stock Exchange, Inc.; Chicago Board Options Exchange, Inc.; and Pacific Stock Exchange, Inc.; Order Approving Proposed Rule Changes and Notice of Filing and Order Granting Accelerated Approval of Amendments Thereto Relating to Buy-Write Option Unitary Derivatives (Release No. 34-36710)

- Smith, D. M. (1996). Prime and score premia: Evidence against the tax-clientele hypothesis. Financial Management, 25(4), 46–57.

- Walter, D. H., & Strasen, P. A. (1987, April). The Americus Trust “Prime” and “Score” units. Taxes–The Tax Magazine, 65(4), 239–247.